“Bangladeshi schools achieved only 42.2-74.6% of school days, missing about one-fourth to more than half of the required instruction days in the 2024 academic year.”

For years, I have been deeply involved in education research, working to understand and improve how learning happens in different contexts. Recently, I (along with my research team) began collaborating with Bangladesh’s Department of Secondary and Higher Education (DSHE) on a study to explore whether digital education can be effectively integrated into the regular classroom curriculum. It’s an exciting project, but along the way, I stumbled upon a surprising and concerning realization: the actual number of functional school days in Bangladesh.

Every time I spoke with ministry officials or my research associates, I heard about yet another reason schools were closed. First, it was Ramadan. Then, schools shut down to host SSC examinations. Soon after, there were closures due to floods. And when those weren’t the reason, it was unannounced holidays caused by local elections. Each time, I wondered: how many actual days are Bangladeshi students in school? How do schools manage to complete the academic curriculum on time? What does this mean for their learning outcomes, and what can be done to address it?

These recurring questions sparked the idea for this blog post. In this blog, I will dig deeper into the realities of school closures in Bangladesh, explore their impact on education, and discuss why this issue deserves urgent attention.

In focus: What is the actual number of functional school days in Bangladesh?

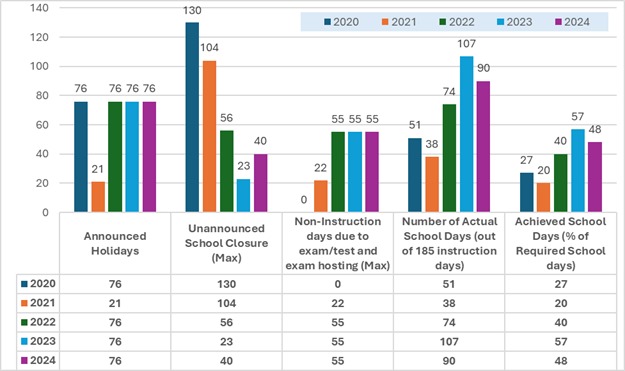

The UNESCO Glossary of Curriculum Terminology outlines various categories of learning and instruction time. Here, however, we steer clear of technical jargon like “learning hours” or “instruction time” and focus on a simpler concept: functional school days. According to the National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) of Bangladesh, the standard academic calendar spans from January 1st to December 31st and proposes 185 school days. This calculation accounts for two-day weekends (Friday and Saturday) and 76 pre-scheduled holidays, including winter/summer vacations and religious observances. Yet, one critical question arises: Have we truly achieved 185 instructional days in recent years in Bangladesh?

The problem: Unannounced Holidays and School Closure

Take the current academic year, 2024, as an example. This year, schools in Bangladesh faced significant disruptions, including one major unannounced closure during the student-led movement from July 16 to August 18, lasting 23 days. Additionally, there were partial closures in various regions due to extreme weather events: a cold wave (January 16–23), heat waves (April 29–May 2 and May 4), Cyclone Remal (May 27), and floods (June 30–July 6 and August 21–September 5).

As a result, the total number of school closure days in 2024 increased from the planned 76 to at least 99, factoring in nationwide non-instructional days caused by political protests. Depending on the location, this number could rise to 128 days. However, additional “hidden” non-school days further escalate this figure. For example, hosting the SSC examination accounted for 19 days, while half-yearly and final exams added 24 days (12 days each). These bring the total to 128–171 non-instructional days, resulting in 47–95 extra days without classes. Moreover, higher secondary school grades often suspend regular classes for SSC preparation and test exams (12 additional days). Altogether, Bangladeshi schools in 2024 achieved only 42.2–74.6% of the 185 required school days – missing about one-quarter to more than half of the necessary instructional time.

Some might argue that 2024 is an outlier, but a look at the 2023 academic year reveals a similar pattern. In addition to the planned 76 school closure days, there were disruptions from Cyclone Mocha (May 14), teacher strikes for the nationalization of secondary schools (June 11–13 and July 11–August 1), and floods (August 8–10). Non-instructional days for exams, SSC hosting, and test preparations added 43–78 more non-school days. Consequently, schools achieved only 57.8–76.7% of the required instructional days, again missing about one-quarter to half of the school year. Furthermore, the first few weeks of January are often consumed by administrative tasks such as textbook distribution, enrollment finalization, routine setting, and teacher training—especially with the introduction of a new curriculum in 2023. This effectively reduces the academic year to just 4.5 to 5 months of functional schooling. Figure 1 illustrates the year-by-year comparison of functional school days since 2020.

The Consequences: School Attendance and Learning Loss

Bangladesh endured one of the world’s longest school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic, lasting 575 days.1 While digital and media platforms, along with interventions such as Telementoring and homeschooling, offered potential ways to mitigate learning losses during this period (Hassan et al., 2024), access to digital educational programs was far from universal. Unequal internet access across the country posed significant barriers; in 2023, only 45% of individuals in Bangladesh used the internet, compared to the global average of 67%. Even within Bangladesh, connectivity varies significantly by region, with only 18% of households in the Rangpur division having internet access.2

A recent CAMPE (2023) study revealed that over a quarter of Grade 8 students failed to meet expected proficiency levels in Bangla, English, and Mathematics on curricular benchmark tests following the pandemic. During the pandemic year, students were automatically promoted to the next grade without achieving adequate learning competency.3 This puts students—especially those from economically disadvantaged households—at a greater risk of dropping out.

Bangladesh’s post-pandemic education state is far from encouraging; in fact, it presents a stark and troubling reality. With only half of the functional school days achieved and the introduction of a new textbook and curriculum in 2023, the general education system faces significant strain. A nationwide study of 455 secondary schools conducted by Fujii et al. (2024) team revealed a worrying decline in student attendance. In November, a critical month for preparing for high-stakes grade-progressing final exams, an average of 41.66% of students were absent from school on any given day. This alarming trend highlights the urgent need to address foundational issues in school days, attendance and active teacher-student-parent engagement to prevent further setbacks in student learning outcomes.

Additional potential issues: Confusion with the new Curriculum

In 2023, Bangladesh launched a competency-based curriculum to shift education from rote memorization to practical, skills-focused learning. While the initiative is interesting, it is deemed impractical given the setting of general school education in Bangladesh. Moreover, its implementation faced several challenges and delays (partially introduced for lower secondary grades in 2023 and partially for the higher secondary grades in 2024). Teachers – undertrained and unprepared – struggled to adopt new curricula and teaching methods and did not get enough training and preparation time to learn how to teach the class best. For example, NTCB recommended keeping the seventh period of school routine empty to be allocated for group activities for activity-based learning (or experiential learning), as introduced in the new curriculum. However, in our ongoing study (Fujii et al. 2024) collected school routines from the sample school and many schools did not seem to implement the NTCB-recommended class routines in Bangladeshi schools, and instead, some used the seventh period for regular classes. See, for example, Figure 3 to understand what a typical school routine in Bangladesh looks like.

Moreover, the new interim government introduced significant changes to the student assessment process midway through the academic year, resulting in students facing half-yearly assessments under a newly implemented system, followed by final exams under a revised framework. For example, at the beginning of 2024, the evaluation system for Class 9 placed a strong emphasis on continuous assessments, which accounted for 60% of the total grade, with summative exams making up the remaining 40%. While this approach aimed to prioritize activity-based learning, it posed considerable challenges for teachers, many of whom struggled to implement it effectively, and left students feeling overwhelmed. By July 2024, the system was revised once more, reverting to a more traditional structure that increased the weight of summative exams to 70% and reduced the continuous assessment component to 30%.

The confusion surrounding these frequent changes extended beyond students and parents, leaving schools and teachers equally perplexed by the abrupt shift back to traditional exams. Delays in finalizing assessment methods further exacerbated uncertainty, creating significant doubt among all stakeholders. Additionally, strong skepticism persists regarding the efficacy of the new curriculum, particularly its removal of the traditional divisions among Science, Humanities, and Commerce streams for students up to Class 10. Critics argue that this shift may hinder the ability to adequately prepare students for STEM education and the demands of 21st-century job markets.

Ideas for solutions: The way forward

Imagine primary school graduates who started secondary school in 2020. This cohort of students experienced 1.5 years of school closures, automatic promotions to higher grades without adequate preparation, and the introduction of a new (and confusing) curriculum in 2023 while in Grade Eight. Adding to this, they endured roughly 50% non-functional school days during the 2023-24 academic years. Now, as they prepare to sit for the SSC examination in 2025, one critical question that arises is: How will this cohort of students (and other adjacent affected cohorts) attain the necessary learning competencies to navigate the demanding HSC curriculum and challenges in tertiary education?

In alignment with the focus of this blog, three key policy recommendations are proposed as follows:

- Ensure Minimum School Days: Mandate a minimum number of functional in-school days with teacher-led instruction to maintain consistent learning opportunities.

- Adapt to Disruptions: Implement flexible and decentralized academic calendars to recover lost time due to climate events, political unrest, or other disruptions, through extended school hours, reduction in holidays (or weekends), or introduction of supplementary programs.

- Keep Consistency: A stable curriculum and assessment system are essential for fostering a predictable learning environment. Drastic or frequent changes disrupt both students’ academic progress and teachers’ ability to deliver quality education effectively.

Written by: Abu S. Shonchoy, Associate Professor of Economics, Florida International University, USA

Acknowledgment: I want to express my gratitude to Mushfiq Sumon of the MOMODa Foundation for his invaluable assistance with data compilation. I also thank the field enumerators for granting access to the photographs, which greatly enriched this work. I would like to thank my incredible research team—Tomoki Fujii, Christine Ho, and Rohan Ray—for their unwavering support of the ongoing research project.

Reference:

CAMPE, “Post-Pandemic Education Recovery and Renewal of School Education,” Technical Report 2023.

Fujii, Tomoki, Christine Ho, and Abu Shonchoy. 2024. “Access or Mandate? A Field Experiment on Digital Learning Resources in Schools across Bangladesh.” AEA RCT Registry. November 12.

Hassan, Hashibul, Asad Islam, Abu Siddique, and Liang Choon Wang, “Telementoring and Homeschooling During School Closures: A Randomised Experiment in Rural Bangladesh,” The Economic Journal, March 2024.

Footnotes:

- https://ourworldindata.org/covid-school-workplace-closures ↩︎

- Even within Bangladesh, connectivity varies significantly by region, with only 18% of households in the Rangpur division having internet access. ↩︎

- https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/education/secondary-students-be-auto-promoted-147817 ↩︎